That's what an elite runner told the author after a Boston half marathon when he saw him in his funny-looking "minimal" running shoes. As he limped away, David Abel wondered why the shoe company hadn't told him the same thing.

| ||

|

By David Abel | Globe Staff | January 9, 2011

There I was, just as the promotional literature promised, effortlessly gliding along the wooded path. It really did feel liberating to run with next to nothing between my feet and the ground. After three marathons and decades of running in weightier shoes, each of which seemed to yield a different injury, I had decided to give “minimal” shoes, the latest running fad, a try. After all, researchers at Harvard University had shown that running barefoot could reduce injury rates by encouraging runners to strike the ground with a more natural gait.

So last summer I started training in a new pair of $85 Vibram FiveFingers. Vibram, an Italian company with its North American headquarters in Concord, has already sold about 2 million of its peculiar shoes, which have almost no cushioning and look like gloves for feet – nearly 70 percent of them in the past year, including to Senator Scott Brown. And it expects to sell as many as 2.5 million this year. The shoes have also spawned new product lines, at companies from

On my first run, the FiveFingers sounded odd as my feet slapped the pavement in the thin rubber soles. But they weigh only ounces, and I felt an almost giddy lightness as I strode toward my trail in Jamaica Plain.

I was recovering from a knee injury, and it was nice to feel the stress on a different part of my body after a litany of other nattering hurts, from plantar fasciitis to hip pain.

But as I left paved road for dirt trail, I got my first lesson in the limits of minimal running. I landed on an angular rock concealed in the dirt, which felt as if a needle had been thrust into my heel. The pain had just begun wearing off a few minutes later when I landed on a stone hidden beneath fallen leaves – same foot, same spot. To say that I wanted to cry would understate how much it hurt.

Over the next few weeks, I learned about other perils of running with the shoes, especially as acorns began to fall. There were the small gaps and loose bricks on sidewalks, steel bumps to warn the blind at street corners, and potholes galore, all of which presented hazards that I was pleasantly oblivious to when I wore my old running shoes.

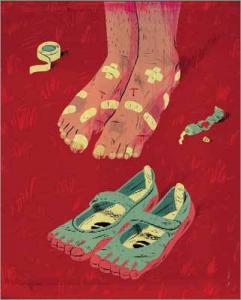

When it rained, it was fun to prance through the puddles without carrying the soggy weight of socks and sneakers. But the rubber dug into my feet, producing blisters and bloody cuts, and the moisture caused a less-than-aromatic odor in the shoes, even after I washed them with detergent.

Then I began to feel a twinge in the bridge of my right foot.

The more I ran in the FiveFingers, the more I questioned the claims about them. Some minimal-running advocates argue that “motion control,” “stability webbing,” and other newfangled design elements of typical running shoes can cause injuries. But I wondered about the dangers of running in the city with just millimeters of protection between my sole and the street.

I chalked up my initial pain as inevitable, and committed to sticking with the shoes at least until the Boston Athletic Association’s half marathon in October. But I also looked online to see whether anyone else had the same concerns. Surely with tens of thousands training for the 2011 Boston Marathon, I couldn’t be the only one wondering about this minimal-running craze.

When I contacted him, he said he and his colleagues had seen “a rash” of injuries from people running barefoot or in minimal shoes. He has called on Christopher McDougall, author of the 2009 bestseller Born to Run, which became the doctrine of barefoot running, and Harvard professor Daniel Lieberman, a human evolutionary biologist whose research on barefoot running has added momentum to the fad, to stop advocating minimal running for the masses.

“This is definitely not for the majority of runners,” Kirby said. “The Vibram FiveFingers are boat shoes; they were never meant for running, and it seems like there’s a strong correlation [between] running with them and stress fractures. They should be banned from being marketed to runners, because they are causing injuries – not preventing them.”

So I called Lieberman. He told me he doesn’t suggest that all barefoot runners or those using FiveFingers will escape injury. He said studies have shown that between 30 percent and 70 percent of all runners each year suffer a repetitive stress injury. “The idea that if you run barefoot you will no longer get injuries is ridiculous,” said Lieberman, whose research has been sponsored in part by Vibram. The truth, he said, is there have been no studies comparing injuries of shoe-clad runners with those unshod or running in minimal shoes.

And yet he repeated the mantra of barefoot runners: People ran for thousands of years without shoes, or with minimal soles, and only in the past few decades have we started running with arch supports, medial posts, and the high, cushioned soles of modern shoes. He said his research shows that running barefoot makes it more likely that runners will strike the ground with the ball or middle of their foot rather than their heel, reducing the jarring impact on the body.

“My assumption is Mother Nature is a better engineer than any human engineer,” he said, “and we know running shoes are failing a lot of people.”

With my own pain lingering, I wondered whether Mother Nature had ever stepped on a sharp rock while jogging barefoot.

Tony Post, the CEO and president of Vibram USA, began wearing FiveFingers about six years ago after sustaining a knee injury. He has run long distances in the shoes and says he has not suffered an injury while using them that has prevented him from running.

I asked whether his company had done any research about the effects of running long distances with such shoes, and he said it is sponsoring studies. But he added Vibram needs to educate people about how to use FiveFingers. Even though the company markets the shoes at marathons, he said they were never meant exclusively for running.

“We don’t tell people to run long distances or not to run long distances,” he said. “That’s a personal choice. . . . But there are going to be problems along the way. Not every shoe works for everyone. It’s an unfortunate consequence of the sport.”

He said he is not a coach and does not provide running advice. “I think everyone’s different. It’s hard to have one set of advice for everyone.” But then he added, “We need to dedicate more resources to educate people about how to use our product.”

So I asked what kind of education they might provide.

“We encourage people to go gradually and to listen to their bodies,” he said, referring to the advice given on the tag that comes with the shoes. “The challenge is to know where the limits are.”

As the months wore on, my feet seemed to adapt. I developed a cushion of calluses below my toes and on my heels. I no longer felt every pebble or rut in the road, and my calf muscles seemed to strengthen. Two months after I began the experiment, I was logging 10 to 12 miles on longer runs. My knee pain had vanished. Aside from random aches and some post-run tenderness on my soles, I felt the shoes were working – that I was running more lightly on my feet, with less pain radiating through my body. The only thing I couldn’t shake was the persistent pain in the bridge of my foot.

It felt like a kind of reverse plantar fasciitis, one of the many running injuries I have experienced over the years, as the pain was most acute when I woke up in the morning. The twinge of discomfort disappeared as the day wore on and often when I ran. But it always returned.

A few weeks before the half marathon, I decided to rest my feet and train with my old New Balance shoes. I began icing my foot, and the pain seemed to subside. But as soon as I began wearing the FiveFingers again, the pain returned.

Finally, a week before the race, I visited my doctor and had an X-ray. It didn’t reveal any sign of a serious problem, and given my history of minor aches and the idea I had come to believe – that serious runners have to reconfigure their relationship to pain – I decided to stick with my plan. I would run the half marathon in the FiveFingers.

The morning of the race was cool, and after wiggling my toes into the shoes, I stood with thousands of others shivering in dew-covered grass. It felt as if my feet were bound in ice.

When the gun fired, a friend and I made our way through the pack. I still felt tenderness in my foot, but it was bearable. The main problem was that my frigid toes were numb. The pounding quickly woke them up, but not before one of my toes caught on the pavement and I took an embarrassing, but minor, tumble. From there, the run went as well as I could have hoped, though I could still feel the grooves in the pavement with every step. I seemed to gather strength and pick up speed in the later miles, truly appreciating the weightlessness of my feet, which made running uphill easier, especially toward the final climb of the race.

With less than a mile to go, we zigzagged though the Franklin Park Zoo, and I found myself on a dirt trail littered with stones. My feet had taken a beating, so I tiptoed over the path as if I were stepping around broken glass.

I sprinted over the finish line, but as soon as I stopped, it felt as if I had rocks in my shoes. I had massive blisters. And if that weren’t enough, the top of my foot felt as if someone in stiletto heels had stomped on it.

Limping toward the first-aid station, I encountered three Kenyans who had been among the top finishers. They pointed at my feet, and I noticed that they were wearing ordinary running sneakers.

“Did you really run in those?” one asked.

“I did.”

“We used to run barefoot to school every day, until we got shoes in high school,” he said. “But we used to run on dirt and grass. We would never run like that on pavement.”

He paused and laughed. “You’re crazy.”

I spent the rest of the day with ice wrapped around my foot and taking ibuprofen. And the next day I went for an MRI. I had a stress fracture on the second metatarsal of my foot.

A few days later, I visited Dr. Naven Duggal, an orthopedic surgeon who sees a lot of injured marathon runners at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. He said I had to stop running for six weeks, and, shaking his head, he told me how he and other doctors he works with had seen an increasing number of patients with the same stress fractures after running barefoot or with minimal shoes. The danger with something like FiveFingers, he told me, is that a lot of competitive runners seeking an edge or a way of avoiding their perennial pains are taking to a fad without any real evidence of whether it will do more good than bad. Duggal, for one, is suspicious.

“It’s hard to make the direct association that they cause stress fractures,” he said. “But if you put the dots together, you can make the association.”

Then he sent me to get fitted for a special boot, with a thick, rigid sole.

Back home, as I hobbled around, pining for the fix of a long run, I found a new use for my FiveFingers. The scuffed soles fit snugly inside my open-toed boot, keeping my bruised foot taut and toasty.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.